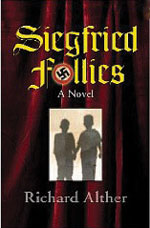

“Siegfried Follies” by Richard Alther (Regent Press, 2010) In his second novel, “Siegfried Follies,” Richard Alther explores the nature of cultural and religious identity. The novel follows the intertwining lives of blonde, blue-eyed Franz and J, a Jewish boy, in Nazi Germany. The plot spans nearly 30 years, but the novel’s scope is far broader; it reaches back to the beginnings of German and Jewish culture and asks fundamental questions about nation, race and family, drawing from sources as disparate as Wagner, “Mein Kampf” and the Torah.

In his second novel, “Siegfried Follies,” Richard Alther explores the nature of cultural and religious identity. The novel follows the intertwining lives of blonde, blue-eyed Franz and J, a Jewish boy, in Nazi Germany. The plot spans nearly 30 years, but the novel’s scope is far broader; it reaches back to the beginnings of German and Jewish culture and asks fundamental questions about nation, race and family, drawing from sources as disparate as Wagner, “Mein Kampf” and the Torah.

The novel opens with a young Franz working diligently at a Munich hospital, where he struggles with conflicting feelings of nationalist pride and horror at the mistreatment of the hospital’s patients. His life is given a clear and sudden purpose when, after barely escaping an air raid on Munich, he rescues J and takes it upon himself not only to nurse the boy back to health, but also to create a new family with him. The novel follows their life together and their lives apart as unlikely brothers after the war’s end. Franz plays the part of the ambitious breadwinner while J takes on the role of artist and scholar, and each is ultimately driven to deep introspection that leads to thorough exploration of the cultures from which they came.

Alther’s probing into the meanings of brotherhood, race and national identity is thoughtful and thought provoking, but the facility with which he imbues his questions into plot and prose is inconsistent. At times, the conflicts as played out in the characters’ minds and actions are vivid and compelling: in one quiet, elegant scene, J ponders the importance of community and ritual as he transforms a Jewish-American family’s tool shed into a sukkah. But often the questions come out murky, the conclusions preachy or pedantic. Save for a few poetic gems (empty guard towers described as “gaping scarecrows”), the prose is lucid but unremarkable. Sex, one of the novel’s frequent topics, is addressed bravely but not deftly, and the few truly tender, human moments are counterbalanced by an abundance of awkward genital metaphors and a general sense of trying too hard. Franz and J are on the whole believable protagonists whose motives ring true, but too frequently they come off stilted and predictable, like props whose sole purpose is to ask the questions and address the conflicts that interest the author. The flow of events in the narrative is choppy, and though it is easy to become engrossed in an individual scene, overall the pacing is uneven. It can become easy to forget that this is all one story.

Despite its missteps, “Siegfried Follies” is notable for being unlike any Holocaust-related book I have read. Neither polemic nor maudlin, it is academic in scope and poetic in tone. The story is a good one, even if the telling is at times pedestrian. The novel reaches toward being a grand literary statement; this it falls short of, but it remains an interesting story plainly told.