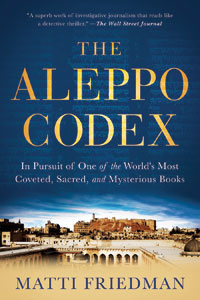

“The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible” by Matti Friedman. Algonquin Books, 2012, $24.95

The winner of the 2012 American Librarian Association Sophie Brody Medal for the best Jewish book is “The Aleppo Codex” by journalist Matti Friedman. Friedman’s book is a work of non-fiction that is more thrilling than many contemporary thrillers.

The winner of the 2012 American Librarian Association Sophie Brody Medal for the best Jewish book is “The Aleppo Codex” by journalist Matti Friedman. Friedman’s book is a work of non-fiction that is more thrilling than many contemporary thrillers.More than a thousand years ago in the city of Tiberius, the Codex was created by a scribe named Shlomo Ben-Buya’a under the supervision of another scholar, Aaron Ben-Asher. This book was to be the definitive text of the Hebrew Scriptures — each letter perfect, each word as it should be. It was not written as a scroll, but as a several hundred-paged parchment book, which would be consulted by scholars and scribes throughout time.

More than 100 years later, the Codex was in Jerusalem when the Crusaders sacked the city. It was ransomed and sent to the Egyptian Jewish community of Fustat, outside of Cairo. There it was studied by scholars including Maimonides, who based many of his treatises on the text. Approximately two centuries later, one of Maimonides’ heirs moved the library to Aleppo where, in time, the Aleppo Codex became known as The Crown, and became the most venerated text in the Aleppo Jewish community.

All of the Codex’s ancient history is well-documented. What Matti Friedman investigates is what happened to the Crown of Aleppo after the State of Israel was declared, and the 2,000-year-old Jewish community in Aleppo was forced to flee the wrath of the Syrian Muslims. It is known that the Grand Synagogue was burned, and the box containing the Codex was opened, scattering its pages on the ground. At this point the story becomes murky. Did the Codex burn? If it didn’t burn, who rescued it?

What is definitively known is that The Crown of Aleppo arrived in Jerusalem in 1957, having been smuggled from Aleppo by Murad Faham, a Jewish cheese merchant. It was placed in the hands of Shlomo Zalman Shragai, head of immigration under President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. At some point It was sent to the library of the Ben-Zvi Institute. Later it was discovered that approximately half the pages of The Crown were missing.

Friedman painstakingly investigates the individuals who may have been custodians of the Codex from the time the synagogue burned until the revelation of the missing pages. Some were Mossad agents who helped refugees escape to Israel. Others were merchants, book dealers, librarians, conservators, rabbis, people on the street the day the synagogue burned and Israeli political leaders.

Rather than getting clearer, the mystery of the Codex becomes murkier as the investigation goes forward. For example, there was only one book written about the Aleppo Codex during the first 25 years it was held at the Ben-Zvi Institute. The author of the book was Amnon Shamosh, a popular Israeli novelist who had been born in Aleppo. When Friedman interviewed Shamosh, then an old man, the author indicated that much of what he had written had been censored by the Ben-Zvi Institute turning his book into a whitewashed story in which the Institute was portrayed as the savior of the book — or what was left of it.

It would be unfair to readers to give away the ins and outs of this mystery. The story of “The Aleppo Codex,” as Friedman relates it, has as much adrenaline as a well-written thriller. Aleppo has been in the news lately as a center of fighting in the Syrian uprising. In the past, it was a flourishing Jewish community and a major center of learning and commerce. Memories of the vanished community can be discovered in a cookbook, “The Aromas of Aleppo: The Legendary Cuisine of Syrian Jews” by Poopa Dweck, and also in a book of short stories by Amnon Shamosh, entitled “My Sister the Bride.”

Andrea Kempf is a retired librarian who speaks throughout the community on various topics related to books and reading.