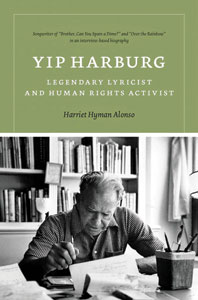

“Yip Harburg: Legendary Lyricist and Human Rights Activist,” by Harriet Hyman Alonso. (Weslyan University Press. 286 pp. $28.95. Also available as Kindle and Nook downloads.)

When I was a child growing up in the Northeast, never imagining I would spend over half my life in Kansas, my one image of this state came from watching Judy Garland sing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in “The Wizard of Oz.” Of course, it was only a Hollywood sound stage, but to me that was Kansas. Now the man who wrote the words to that song, and so many others, is the subject of a new book, “Yip Harburg: Legendary Lyricist and Human Rights Activist.”

When I was a child growing up in the Northeast, never imagining I would spend over half my life in Kansas, my one image of this state came from watching Judy Garland sing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in “The Wizard of Oz.” Of course, it was only a Hollywood sound stage, but to me that was Kansas. Now the man who wrote the words to that song, and so many others, is the subject of a new book, “Yip Harburg: Legendary Lyricist and Human Rights Activist.”

E. Y. “Yip” Harburg’s life story has been told in other books, and Alonso’s purpose is not to duplicate those works. It is rather a discussion of Harburg the creative artist, for the most part told in his own words from the various detailed interviews he gave about the thought that lay behind his work. It should be a must read for anyone interested in the art of lyric writing.

It has often been noted that virtually all of the major composers and lyricists of the classic Broadway musical — with the exception of Cole Porter — were Jewish, but perhaps no one was more deeply steeped in Jewish tradition (though not in traditional religious observance) than Harburg. His father would tell his mother that the two men were going to synagogue, but instead they would go to what Harburg called his “substitute Temple — the theater,” by which he meant the Yiddish theater. I don’t know of any other lyricist who might have said, as he did, “Yiddish has more onomatopoeic, satiric, and metaphoric nuances ready-made for comedy than any other language I know of.”

Though his fame today rests primarily on one film, one Broadway show (“Finian’s Rainbow”), and a handful of songs, such as “Brother Can You Spare a Dime?” and “Lydia the Tattooed Lady,” he earned the reputation of being a lyricists’ lyricist, praised by such writers as Stephen Sondheim and Sheldon Harnick (of “Fiddler on the Roof” fame.) Harburg himself, however, thought of his craft as a means to an end, as a way of expressing his commitment to human rights, believing that a good lyric could make radical ideas acceptable. He greatly admired FDR, and he explained that many of the lyrics in “The Wizard of Oz” expressed his optimism about the New Deal, though there was some social satire as well, as in the Wizard’s comment to the Scarecrow about needing not a brain but a diploma. “Finian’s Rainbow” (1946) was way ahead of its time not only in its satire on the capitalist system but in its confrontation of prejudice against African-Americans. A few years later Rodgers and Hammerstein confronted racism in “South Pacific,” but that show dealt with anti-Asian prejudice, a less controversial subject. It is not surprising that Harburg’s film career was cut short by the infamous blacklist, though he was able to continue working on Broadway.

The most interesting aspect of the book is Harburg’s detailed explanation of his theory of writing and the detailed thought processes behind his simplest songs. “Words make you think a thought,” he explained, “music makes you feel a feeling. But a song makes you feel a thought.” At the end of his life, he became frustrated by the changes in people’s taste: “I’m very sad that those beautiful sweet songs with architecture and structure are not being played now and that they’ve been pushed off the air by songs that are rather vituperative and convulsive.” Nevertheless, we should conclude, as the book does, on a more positive note: “I think the human species has a life force that’s got to prevail and survive and no matter how many follies, foibles, it will…. And so my theme song, the theme that keeps me going all these years, is ‘Look to the Rainbow.’ ”