Lisa Bauman’s first glimpse of the German words “ARBEIT MACHT FREI” (“Work sets you free”) perched in wrought iron atop the front gate of Auschwitz enveloped her in a sinister silence.

“There’s definitely an oppressive feeling that you get,” Bauman said. “There’s something in the energy, the air, the atmosphere — all of it. It just weighs you down. … From that point on, you can’t even talk. There are no words. There’s a hush.”

Bauman is a lifelong Catholic and a teacher. She took that first trip to Auschwitz in 2007 with some of her students from St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic High School in Overland Park, where she taught from 1989 until moving to Blue Valley West, her alma mater, in 2014.

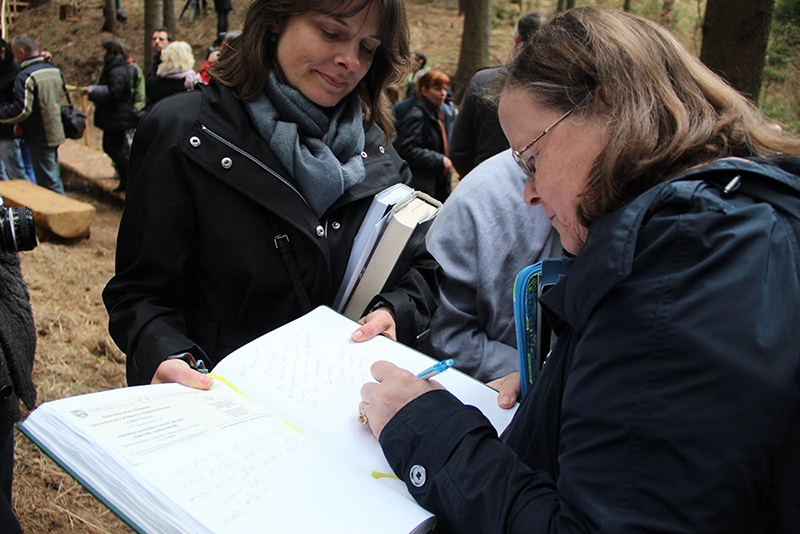

She returned to Auschwitz almost every year through 2014, always with Aquinas students. She also visited sites in Berlin and Prague, including other death camps. Bauman was at Auschwitz the day in 2014 when a white supremacist killed three people at Jewish institutions in Overland Park. None of the victims were Jewish.

“You think about what might’ve happened if more people had stood up instead of being silent, which is a lesson I try to instill in my students,” she said. “Take action.”

As an educator, Bauman has imparted those lessons through classes and student trips. And now similar teachings will be open to a broader audience with the opening next week of the Union Station exhibit, “Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away.”

Bauman hopes to work the exhibit into her curriculum and will encourage students to see it.

The Holocaust was part of Aquinas’ required curriculum, so Bauman immersed herself in the subject. She used the late Elie Wiesel’s “Night” in teaching a course titled “Holocaust Literature: Putting Words into Action” in the mid-1990s.

She took “words into action” for the course title from a poster she had gotten at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. It also read, “It’s not enough to be compassionate. You must act.”

“I brought back that poster and it really became a theme for our freshman year, and it’s been my theme since then,” Bauman said. “It’s not enough to just feel, ‘Wow, that’s terrible that that happened way back then,’ but you have to take action and see the world around you and what’s happening today and do what you can in order to try to repair the world.”

One year, her students got involved in a Holocaust Museum outreach project responding to the Darfur genocide. Her students wrote and sent postcards to then-President George W. Bush about saving Darfur.

Through the Midwest Center for Holocaust Education (MCHE), Bauman invited Holocaust survivors to speak to her Aquinas students, which “was life changing for me.” The survivors usually wanted the students to ask questions and would pose with them for photos.

“It was powerful,” Bauman said. “The kids always responded. Tears, hugging, the survivors giving them personal messages (such as) ‘You can do this. Whenever you’re feeling down about something, you have the strength inside you. If I can do this, you can do this. Go out into the world and fight against hatred and make sure this never happens again.’”

Speaking to the students was also hard on the survivors because of the trauma they had suffered and how it had changed their lives, she said. They often had trouble sleeping the night before and took days to recover afterward.

“I still have students who I’m in touch with from decades ago who … say ‘Your class changed my life; this class was the best thing I ever did,’” Bauman said.

Charlie Sullivan’s life was one of those changed by a trip to Europe with Bauman during his junior year at Aquinas in 2009 and again in her Holocaust class his senior year. He is 29, grew up in Olathe and now lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“Mrs. Bauman is very big on action,” Sullivan said. That translated to “How do you take this information and integrate it into your life?”

That question prompted him, as an undergraduate studying mechanical engineering at the University of Nebraska, to do research with the school’s history department on the long-term effects of Holocaust education. Later, while studying for a master’s degree in computer engineering at the University of Texas at El Paso, he volunteered at a Holocaust museum near his home.

“I got a complete change in world view,” Sullivan said of the European trip and Bauman’s class. “It has made me develop an understanding of the capabilities of humans and what kinds of things make things like the Holocaust possible. … There probably isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t have some sort of thought that is related to that. … It’s painted how I view politics, relationships, everything.”

While teaching at Aquinas during the 1998-99 school year, Bauman did a one-year fellowship at the Holocaust museum. It included one summertime week learning about the Holocaust at the museum, along with talks presented by historians and other teachers.

As part of the fellowship, teachers worked the Holocaust into their curriculums or did a project with their students. Bauman and her students built a website with information the students learned about the Holocaust.

Bauman made a PowerPoint presentation from a photo slideshow a Holocaust museum teacher had been presenting at workshops. She and another fellow, a history teacher, applied for a museum grant and created the PowerPoint together, with “the lens of English and history.” Then they made it into a CD-ROM and mailed it to teachers all over the country.

Stephen Feinberg oversaw that project as the fellowship’s supervisor. He recently retired and lives in Minneapolis. He also has a Kansas City connection with Jean Zeldin, former executive director of the MHCE; they worked together on a traveling exhibition that came to Kansas City.

Feinberg said he saw something special in Bauman during her fellowship, that her literary and historical knowledge made her an “outstanding teacher.”

“It was fairly clear to me very early on that Lisa combined exceptional academic and organizational abilities with outstanding personal skills,” he said.

Bauman’s fellowship also qualified her to travel regionally to instruct other teachers how to teach the Holocaust in one-day workshops at universities, which she did from 2005 through 2013.

At Blue Valley West, Bauman teaches English and a global education course titled “Global Citizens: Awareness to Action.” She incorporates the Holocaust in those classes. She also received a Fulbright Teachers for Global Classrooms Program grant in 2019.

Bauman also has taught at Baker University since 2014. She teaches a course for graduate students in education called “Fostering Conscientious, Courageous Global Citizens,” which instructs them how to teach about the Holocaust.

Bauman was born and raised in Lawrence and lives in Overland Park. She is a member of St. Pius X Catholic Church in Mission.

She received a bachelor’s degree in English with a minor in secondary education from Saint Mary College in Leavenworth (now the University of Saint Mary) and a master’s in education, teaching and leadership from the University of Kansas.

She and her husband, Boyd Bauman, have five children, ages 8 to 34.

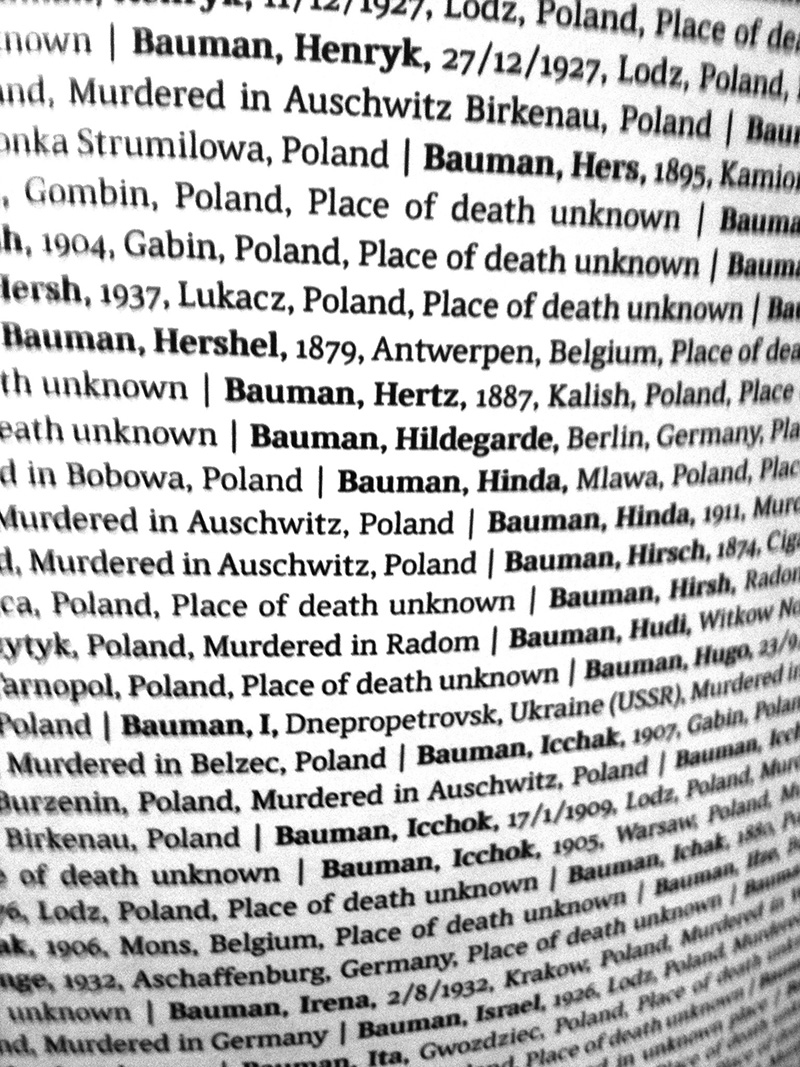

Bauman wants to further research her husband’s surname. She found records from the late 1800s that show his family had spelled it Baumann. She suspects that, from fear of antisemitism, his family might have dropped the final “n” in their name to make it appear less Jewish. Her husband’s grandfather was a member of the Apostolic Christian Church.

“Whether or not there is Jewish ancestry, people were afraid of repercussions if people thought they were Jewish, and they might’ve had a hard time,” Bauman said. “I think it’s sad that to this day, anti-Semitism is such a problem, and that people have to be afraid for their religious identity. …

“Jewish kids do have to be careful,” she said. “Not just Jewish kids but lots of kids, based on identity. That’s also part of why it’s important to study this history.”