Singapore’s Jewish history is palpable on its streets: There’s Manasseh Lane and Meyer Road, named for the hugely influential Manasseh Meyer, a Baghdadi Jew and early leader of the Jewish community who helped open two of its Sephardic synagogues.

Along Middle Road, 19th-century buildings bearing Stars of David and the names of the Jewish businessmen who built them line the street, marking what used to be the Jewish “Mahallah,” or neighborhood, where 1,500 Jews lived during the middle of the 20th century.

In fact, in the southeast Asian city of 5.7 million — mostly ethnic Chinese, Malay, and Indian migrants and only 2,500 Jews — countless roads and monuments in the city-state are named for influential Jews of the past and their achievements.

But in their 200 years of rich history, the Jews of Singapore have never had a place of their own to show off the story of their people, until now. In the old Mahallah and on the ground floor of the Jacob Ballas community center — named for the Iraqi Jewish philanthropist who chaired the Singapore and Malaysia stock exchange in the 1960s — a new museum tells the full story of Southeast Asia’s oldest continuing Jewish community, beginning with the arrival of the first Jew in 1819.

“It’s really important that Singaporeans know the part that the Jews have played in the 200 years of history, and it has been significant,” said Ben Benjamin, a member of Singapore’s Jewish Welfare Board who spearheaded the museum. “We wanted to demonstrate that not only about the Jewish people in Singapore, it’s about how ‘Singaporean’ Jews are.”

The Jews of Singapore Museum captures the story of a community that has waxed and waned in size, even as Singapore has grown rapidly. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the local Jewish population was made up largely of emigres from Iraq and Europe who came to Singapore to evade antisemitism and pursue trade, including Benjamin’s family. By the mid-20th century, before World War II, the community grew to 1,500 Jews before beginning a steep decline; fewer than 200 lived there by the 1960s.

Today, a record 2,500 Jews call Singapore home. But even as some of the old Baghdadi trading families remain — Benjamin is a fifth generation Iraqi-Singaporean Jew — the majority of local Jews now are a diverse mix of more recent Hebrew- or English-speaking arrivals who have come to invest in one of the world’s tech and financial hubs.

The historic heart of Singapore’s Jewish community, though, “unfortunately, will continue to shrink,” Benjamin said, and the museum is an effort to preserve it.

The museum highlights a time when some of Singapore’s most important figures were Jewish, such as David Marshall, who became the city-state’s first chief minister in 1955. Guests can scan QR codes to hear the voices and speeches of Marshall and other figures, and view videos, photographs, and artifacts from the community’s rich past and present.

“Some really interesting things were actually uncovered during the curatorial process,” Benjamin said. Curators found photographs of unknown Jewish properties like a resort far in Singapore’s west, far from the Mahallah.

“It’s now been completely demolished to make way for what is Singapore’s industrial heartland,” he said. “We didn’t know this until this museum was put together.”

Based on a book commissioned by the community and published in 2007, the museum is the product of three years of work and preparation only further delayed by the pandemic. Finally, on Dec. 2, the museum opened to the public.

“We hope that the history of our forefathers, most of whom had fled persecution from Iraq to settle and thrive in Singapore, will be a reminder of the importance of welcoming strangers in our midst, and of strengthening unity and solidarity among adherents of different religions,” Nash Benjamin, president of the Jewish Welfare Board and uncle of Ben Benjamin, said at the opening.

The exhibition is also available to all via a virtual tour on the museum’s website, where guests can walk through the museum and interact with the exhibit digitally. For non-Jewish Singaporean community members, a section of the museum is dedicated to illustrating Jewish festivals, culture and religion.

This year was a tumultuous one for Singapore’s Jews. In March, the Jacob Ballas Center, now home to the museum, hosted a press conference to announce the arrest of a radicalized Singaporean soldier who had planned to kill at least three Jewish men as they left the Maghain Aboth synagogue. (The community is mostly divided between the two Sephardic Orthodox synagogues built over 100 ago, Maghain Aboth and Chesed-El, in addition to a smaller Reform congregation made up of mostly Ashkenazi Jews.)

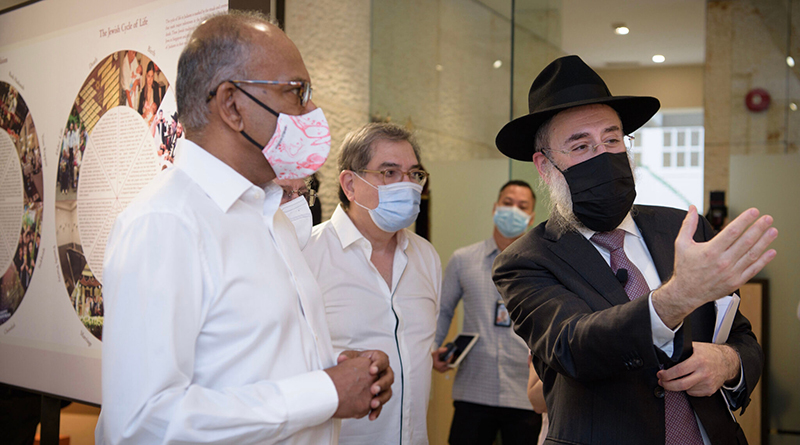

Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam, who revealed the planned attack nine months earlier, spoke at the museum’s opening event.

“As minister for home affairs, I have said more than once to you, that the safety and security of all in Singapore, including the Jewish Community is a key priority,” he said.

Singapore, known globally for harsh legislation, had “very high” levels of government restrictions on religion in 2019, according to the global Government Restriction Index, despite its constitutional guarantee of religious freedom. In the same year, however, it had low levels of social hostility toward religion.

Benjamin says the Jewish community has always felt safe, protected, and supported by the greater community and the government of Singapore, whose National Heritage Board granted up to 40% of the funding to the Jews of Singapore Museum.

The planned attack earlier this year, he said, came as a shock to Singapore’s Jews.

“Life carries on. We feel very safe, very supported in Singapore,” he said. “And I think we owe it to ourselves, to the community of 200 years to carry on trying to build and allowing this community to thrive.”

Virtual visits to the Jews of Singapore Museum can be scheduled online.