A lost Jewish history has been reclaimed and was unveiled on Jan. 10.

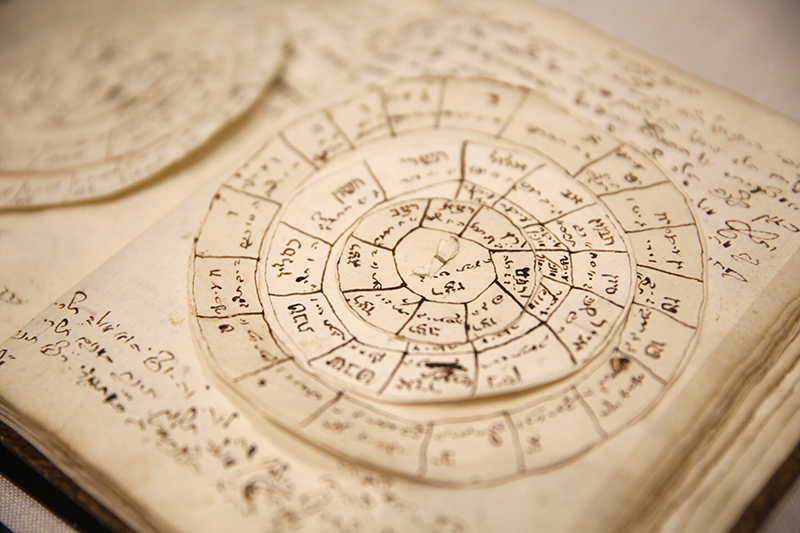

For the first time, more than 4.1 million pages of original books, artifacts, records, manuscripts and documents—cultural survivors of the Holocaust—have been digitally reunited through a dedicated web portal and now accessible worldwide. It includes everything from copies of the rarest sermons of 18th-century Chassidic rabbis to a singular collection of Yiddish pornography.

The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (YIVO) announced that it has completed the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections Project (EBVOCP)—a seven-year, $7 million initiative to process, conserve and digitize YIVO’s divided pre-World War II library and archival collections. According to YIVO, the project is the first of its kind in Jewish history, and sheds new light on prewar Jewish history and culture throughout Eastern Europe and Russia.

“It’s very difficult to understand how little we truly know, especially in the United States, of what that past was. For most of us, what we know is handed down from our grandparents or great-grandparents who may have come from Eastern Europe,” Jonathan Brent, CEO of YIVO, told JNS. “That is to say that most of us know a family history. And even that, in my case for instance, was confined to the fact that I knew my one set of grandparents came from Zhytomyr and another from Chernigov. They lived basically in mud holes and were humiliated most of the time, and that was it. That was the culture that I came from.”

“And so, now comes the fact that we now can reveal for Jewish people of Ashkenazi descent all over the world what the real splendors of that civilization were for 1,000 years—a civilization that took pride in itself, a civilization that had aspirations, that had ambitions, that had tremendous driving force and a civilization that encompassed not just the pious and not just the victims of antisemitism, and not just the poor and impoverished people from whom so great a proportion of America Jewry derives, but rather, a people that spanned the entire gamut of human experience,” said Brent.

This project is an international partnership between YIVO and three Lithuanian institutions: the Lithuanian Central State Archives, the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania and the Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences.

In 1941, the Nazis ransacked the YIVO Institute in Vilna, destroying countless documents. A group of Vilna ghetto workers were forced to sift through the rest, sending select materials to Frankfurt, Germany, for review at the Nazi Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question. Those materials were largely recovered by the U.S. Army and sent to YIVO in New York. Other documents were secretly smuggled out by the ghetto workers and then saved again in 1948 from the Soviets by the Lithuanian librarian, Antanas Ulpis. They remained hidden in the former Church of St. George until they were uncovered in 1989.

Five years ago, approximately 170,000 additional documents were also discovered in the National Library of Lithuania, including rare and unpublished works. Even with some 4 million documents digitized, Brent believes that much more will be discovered.

“We thought the totality of all this had been compiled in 1991,” he explained. “Then, in 2014, a friend of mine in Vilnius told me that I might be interested in stuff in the booklet of Wroblewski Library, which is a library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. So I go there and there is a long table, and on the table are boxes. And in the boxes are documents that are stamped ‘YIVO Institute.’ We thought all of our materials were in the National Library.

“This is all brand-new stuff,” he stated.

“So, I look at the director and I say, ‘You’ve had these since 1948, and you’ve kept them secret? What were you doing with these materials?’ She said, ‘We were waiting.’ I said, ‘Well, what were you waiting for?’ She said, ‘We were waiting for you.’ And it sent a shiver went up my spine. They were waiting for us, and there are still more materials that are waiting for us. And what we have to do is discover them and come and find them,” said Brent.

Stefanie Halpern, YIVO director of archives, told JNS that as recently as 2019, completing the project on time seemed insurmountable. The institute decided then that it was time to open an in-house digital lab rather than contracting out the work. The move coincided with the coronavirus pandemic, giving YIVO staff the opportunity to continue their work from home with fuller control over the process. In July 2020, small rotating teams came into the archives to continue the work until everyone came back in regularly in January of last year.

“The conservators looked at every page—cleaning dirt, mending rips, flattening creases. Then the processing archivists read every document, put them in order, create a description, digitize and upload them, making everything available on the Internet,” Halpern told JNS, explaining that the archive wasn’t built simply for scholarly work but to make everything accessible for the layperson without being overwhelmed by the sheer volume of the collection.

“There is a ton of visual material, so you don’t need knowledge of any of the dozen languages featured. There are hundreds of thousands of photographs that really show you what everyday Jewish life was like. They can be found using the keyword search in our database. Just type in ‘photographs,’ and a list of collections pops up. It is difficult and daunting if you’ve never navigated an archive before, so we also have guides available for how to look through our databases, and the YIVO archivists walk individuals through step by step how to actually do research,” said Halpern.

She said those struggling are encouraged to contact the archives directly, and Zoom research sessions organized by YIVO help those looking for information to find it in real time.

“This project has to do with building the Jewish future,” she said.

“I came from a family in which the past and Eastern Europe was a matter of legend. It was Sholem Aleichem and a few recipes that Bubbe would cook in her pot. As opposed to that, this project has to do with how the future is built on the past and how young people, as they begin to become acquainted with these materials, will discover a world of accomplishment, a world of ambition, a world of excellence, a world of dreaming, a world of scheming.

Brent emphasized the completion of the project further, saying the discoveries depict “a world of everything, and it fortifies your sense of what it means to be a Jewish person. We were not simply the beat-up remnants of a civilization, the victims of antisemitism. It was a dynamic, thriving, self-reflective and ambitious culture.”