Vice president and COO of the Jewish Federation of Greater Kansas City weighs in on worldwide conversation

By Michele Chabin

JTA

When Jewish institutions like JCCs and synagogues shut down this spring due to the coronavirus pandemic, it often felt like a wrenching decision arrived at reluctantly after careful deliberation.

Now, deciding how and when to physically reopen Jewish institutions is proving at least as challenging and fraught.

“In this murky interim period — when the pandemic continues even though lockdown orders are relaxing — how can we safely use our facilities?”

That was the question that 44 representatives from schools, synagogues and other Jewish facilities wrestled with when the Jewish Federation of Cincinnati convened an online meeting in June to discuss reopening, according to its CEO, Shep Englander.

“The discussion was very rich,” Englander said. “We all agreed that according to our Jewish values and tradition, we must put the health and safety of our families and community before any other considerations.”

While some Jewish communal institutions have been physically open – either partially or completely – since May, others are still planning a reentry or expect to remain shuttered for the foreseeable future. Many have sought advice from their local federations and the Jewish Federations of North America, the federations’ umbrella organization.

The Secure Community Network, or SCN, the organization that deals with securing Jewish institutions against outside threats, created a working group focused on reopening planning. Comprising security directors, partner agencies, and experts in health, safety and other disciplines, the group produced guidance materials and documents to assist the Jewish community and other faith-based organizations.

“We are helping many Jewish organizations with detailed scenario planning so they can each chart their most effective course for the future,” said Eric Fingerhut, president and CEO of the Jewish Federations. “We trust our communal organizations to make their own reopening decisions. They know the relative risks and needs of their own members.”

With the circumstances of the pandemic varying in different parts of the country, SCN’s official guide, called “Back to Business: A Jewish Community Guide for Reopening Facilities and Resuming Operations in the Age of COVID-19,” emphasizes that every facility is unique and that “no one else can decide for you when you are prepared to reopen.” The Jewish value of pikuah nefesh – protecting human life – must be a community’s first priority, it says.

“Recognize that many may feel uncomfortable returning, and take care not to pressure anyone to do so,” it says. “Find ways to stay engaged and connected with members who are unable or uncomfortable returning.”

In Cincinnati, the community’s local SAFE Facilities ReOpen group drafted several recommendations. Before reopening, a facility should:

determine how it will clean and sanitize surfaces on an ongoing basis

transition staff working remotely to onsite work while adhering to social distancing

implement entry and screening guidelines for staff and members

supply personal protective equipment (PPE)

implement protocols in case someone working in or using the facility is exposed to or tests positive for the virus

address child care if schools are shuttered.

When the community’s JCC partially reopened, it relocated its fitness center to a more spacious auditorium, and the preschool and summer camp are hosting fewer children than it did prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. The JCC’s senior center remains closed, but social workers are continuing to reach out to elderly members, including Holocaust survivors, and the center provides meals at home in lieu of the onsite senior lunch program.

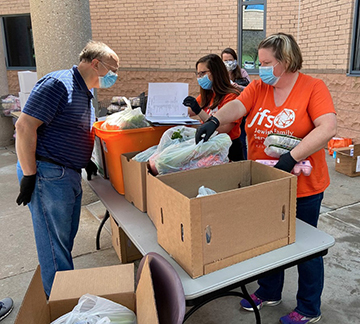

In Kansas City, Derek Gale, vice president and COO of the Jewish Federation of Greater Kansas City, said his federation’s reopening plans are constantly evolving.

“At any given point it’s up to date and then out of date,” Gale said, based on the number of confirmed virus cases in the area, COVID-positive rates and state guidelines. As of mid-July, no more than five people were working onsite at the federation’s offices at any given time, with distancing and other safety protocols in place.

“No one is forced to work in the office,” Gale said, particularly if they are at high risk of suffering virus-related complications. Those working in the office on certain days have discussed in advance with supervisors and notify the rest of the staff in advance.

He also said that the federation recognizes that employees may have child care issues and offers flexibility. Although the local school year traditionally starts in mid-August, the start date is being postponed by state and municipal governments until after Labor Day, and online, remote learning is figuring in to plans of most districts and schools.

The Jewish Federations of North America’s guidance and weekly online meetings with planning experts and other functional area leaders have proved invaluable, Gale said.

In Scottsdale, Arizona, the Ina Levine Jewish Community Campus, which is home to the local federation, Martin Pear JCC, day school and other Jewish facilities, reopened on May 18.

“From the beginning, we took an attitude that it’s about what we can do, not about what we can’t,” said Jay Jacobs, CEO of the campus and the JCC. “The goal was to create an environment people felt safe walking into.”

To get the campus up and running, the facilities director created a reopening plan that was reviewed by a medical task force. The campus held training sessions for all 11 of the facilities it hosts, and the JCC briefed its departments on new protocols.

Ninety percent of the campus’ hallways, staircases and paths now move in one direction to limit interactions and keep foot traffic flowing. In addition to the regular cleaning crew, a full-time crew has as its sole job to sanitize the campus’ doorknobs, railings, counters, sinks, bathrooms, etc. Temperature checks are mandatory for anyone wishing to enter, and signage reminds people with symptoms not to enter the facility.

Before the pandemic, the campus saw some 3,000 to 3,500 people per day. Today it serves about 1,000 daily, including the kids at the Shemesh Camp at The J. Unlike regular summers, there are no field trips this year. The limitations have forced staff and counselors to get creative, come up with activities on the sprawling campus and go “back to the basics” of traditional day camps.

“Things are far from how they used to be, but it’s not all bad,” Jacobs said. For example, taking visitors’ temperatures at the entrance “has reminded us how important it is to greet people when they walk into the building. We’ll definitely continue member greeting once the COVID crisis is behind us.”

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Jewish Federations of North America, which represents 146 local Jewish Federations and 300 network communities. This story was produced by JTA’s native content team.