Low self-esteem. A blurry identity. Isolation. And the need to connect with others, to belong to something, somewhere.

These elements often breed hate. And hate is a learned emotion that leads to learned behavior.

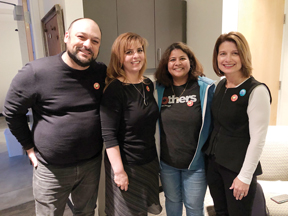

That’s the message former — emphatically former — white supremacists Christian Picciolini and Shannon Martinez shared with an audience of more than 800 at United Methodist Church of the Resurrection (COR) in Leawood on April 11. The event was titled “Is Your Neighbor a White Supremacist?”

Picciolini and Martinez were interviewed on stage by Mindy Corporon. Corporon’s son, Reat Underwood; her father, Dr. William Corporon; and Teresa LaManno were murdered outside local Jewish facilities in April 2014 by a self-described neo-Nazi who had mistakenly thought they were Jewish and shot them. The perpetrator was convicted of the crimes and in late 2015 was sentenced to death.

In response to the crimes, Corporon founded The Faith Always Wins Foundation (FAWF), an organization based on kindness, faith and healing. FAWF (faithalwayswins.org) presented the fifth year of “SevenDays® Make a Ripple, Change the World” (givesevendays.org) from April 9 through April 15. It is the foundation’s annual, local series of events. The events are intended to demonstrate how hatred, bigotry and ignorance can be overcome by kindness, respect and understanding. The event at COR was part of “Day Three: Others.” Jewish Federation of Greater Kansas City and Irv Robinson and Ellen Miller were among the sponsors of the “Day Three” event.

Picciolini and Martinez escaped the cycle of hate they had entered. Now they try to help others do the same.

Picciolini is an author, co-founder of a nonprofit organization called Life After Hate and founder of a nonprofit called Free Radicals Project. He wrote a memoir, published by Hachette Books in 2017 and titled “White American Youth: My Descent into America’s Most Violent Hate Movement — and How I Got Out.”

Martinez is a former neo-Nazi skinhead. For the past 20 years, she has developed community resources to prevent ideologies that lead to hate and violence. She is the program manager for Free Radicals Project and a U.S. regional coordinator for the Against Violence and Extremism Network, a worldwide network of former violence-based extremists and survivors of extremist violence.

Robinson, a member of Kansas City’s Jewish community and a board member of FAWF, told The Chronicle that he had seen Picciolini speak on a “TED Talk” and encouraged Corporon to invite him to speak during the SevenDays events, “as uncomfortable as it may seem on the surface.”

Corporon contacted Picciolini, who told her he was familiar with her story, expressed his sorrow about it and asked how he could help her.

“My response was, ‘I’m not sure I want your help or how you would help.’ ” she said in an interview prior to the event.

Picciolini told Corporon that her story validated his, she said, and that if he couldn’t help the victims of hate in some way, then he wasn’t helping anyone. After consulting the FAWF board, Picciolini and Martinez were invited to speak during “SevenDays.”

Corporon had some trepidation about having Picciolini and Martinez speak as part of “SevenDays,” she said, “but I want to make sure I have the opportunity to portray their story well enough that people understand they are reformed, that they have regrets and that they are working very diligently to make the world a better place.”

She wanted the audience “to understand … that hate is created by people being taught hate, but we as a society can pay more attention to people who are lonely, even alone in a group,” she said.

“Maybe we can see some signs of it,” she said. “They’re a target of hate movements. All of us want to be valued and want to belong. We also want the audience to leave with some action items, through the spoken presentation.”

During the event, Corporon said she had been asked many times why she had invited Picciolini and Martinez to speak publicly. The reason was that “after the murders, I wanted to know why.”

“And what I’m realizing is, I know that I can’t change what happened … but what we can do is we can learn from that and we can help other families not experience the same thing,” she said.

Martinez said that, at age 14, she was “lonely, disempowered and searching.” At age 15, she was raped at a party by two men. All of this, on top of a strained family relationship, eventually led her to join a skinhead group. But the violence associated with the group, and the violent relationships it led her to develop “didn’t fix me; it didn’t make me better.”

Her escape from that life started when the mother of her boyfriend invited Martinez to live with her.

“She chose to look past this vile and hate-filled creature that I had become and instead see me as a hurting and struggling young woman,” Martinez said. “She extended courageous compassion towards me and provided me a place of stability, a place where she would challenge me about … ‘Don’t you want more for yourself than this? Don’t you want to go to college?’ And beyond that, (she) tangibly connected me with the resources to make that happen.”

Picciolini said that when he was recruited into the white supremacist movement at age 14, “I knew nothing about racism.” His parents were Italian immigrants and they lived in an Italian neighborhood. His parents worked seven days a week, sometimes 16 hours a day. Picciolini felt abandoned, wondered whether he had done something wrong that led to his isolation from his parents and had low self-esteem. The group he joined gave him a sense of identity, community, purpose and power.

“I am still looking for vulnerable young people to recruit,” he said, (but now) “I’m trying to rebuild those lives” to help them find identity, community and purpose.

Picciolini “had tormented throughout high school” a black man who worked as a security guard at the school. But the man forgave him “and encouraged me to tell my story. He said, ‘Stop saying you’re sorry and go do something about it.’ ”

The audience had questions for Picciolini and Martinez during the event. One was “How do you best approach people who believe their way is the truth and get them to be open to you and listen?”

Picciolini said that he had learned “to see the child and not the monster. And it doesn’t matter if that child is 16 or 60.” Martinez said that spending one-on-one time and “listening for what broke them” was important for helping them change.

Another question from the audience: What can the average person do to dismantle white supremacy movements?

“We have to embody the change that we want in this world,” Picciolini said. “We have to find a way to muster compassion for people that we think are the most underserving of it, because in all honesty, that is the only thing that I’ve ever seen break hate. (This) does not mean you agree with them. It does not mean that you’re letting them slide. I don’t let anybody slide that I work with.”

Picciolini and Martinez said that they had forgiven themselves but that it was more important to seek forgiveness from those they had hurt.