REHOVOT, Israel — For years, Israeli scientist Tamar Flash has been fascinated with the octopus, and the unusual way the invertebrate’s eight arms propel it effortlessly through the water.

Her interest is no mere hobby. A renowned professor who does research in artificial intelligence at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Flash is using the octopus as a model for methods of diagnosis and treatment of disorders from Parkinson’s disease to autism.

“My major interest is the brain’s representation of movement, or the principles underlying the organization, control and perception of movement by humans,” Flash said. “The octopus has no bones. It’s totally soft. It’s just made of muscles.”

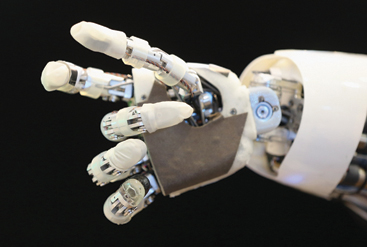

Modeling the movement of the octopus, she said, also may help scientists develop “soft” robots for rehabilitation clinics, search-and-rescue operations and even nursing homes.

“The first generation of robots were made of steel,” Flash said. “But if we want robots to help handicapped people, we had better make them from soft materials that can come in contact with humans without injuring them.”

Flash works at the Weizmann Institute’s new Artificial Intelligence Center for Scientific Exploration, a $100 million initiative. Hers is one of several projects at the center that seek to apply AI principles to real-life problems.

One of the world’s foremost multidisciplinary research institutions, Weizmann is investing heavily in the burgeoning field of AI. Its expertise in computer vision, machine learning and robotics — as well as a culture that encourages collaborations across disciplines — makes AI a natural fit.

More than half a dozen scientists from across the institute do AI-related research at the new center, which was launched about a year ago. The center’s director is Shimon Ullman, a world leader in computer vision who was awarded the 2015 Israel Prize in mathematics and computer science research.

“The techniques coming out of AI — and, more broadly, machine learning — are becoming important in almost all disciplines,” Ullman said. “They can really help scientists deal with huge sets of data in chemistry, in physics and in biology. This will also be very helpful for Israel’s high-tech industry.”

Shai Bagon, an expert in video and image processing, is one of two Robin Chemers Neustein Artificial Intelligence Fellows recruited to work at the center.

“Each one of us has a different perspective,” Bagon said of his fellow researchers. “Some are more theoretical in their inclination, others are more practical. We want to see if by establishing this center we can somehow enable collaborations in fundamental research that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

While it’s not yet clear where the work will lead, Bagon said, his team’s mission is to conduct basic research on AI and machine learning.

“We are not told what to investigate,” he said. “Rather it’s all driven by the curiosity and ingenuity of the researchers themselves.”

The Weizmann Institute’s focus on curiosity-driven research rather than on profit or commercial success grants its scientists an unusual level of freedom to pursue their own ideas and investigations.

For example, Flash has been working in the field of human locomotion and robotics since the early 1980s. She studied at the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology and has a doctorate in medical physics. Over the years, Flash’s work has been funded by the U.S. Navy and the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and more recently by the European Union.

“We need a basic understanding of what it means to have intelligence,” she said. “There’s a lot of hype now about artificial intelligence, but if we want to bring the AI revolution to the real world, we need robotics. When we move, to us it seems so simple. But it’s not simple at all.”

To help Flash and her colleagues, the center employs powerful Nvidia DGX-1 computers and servers that can crunch numbers in hours rather than weeks or months. However, maintaining and upgrading the equipment is costly, according to Bagon.

The center’s establishment is meant to help Israel become a world leader in underexplored areas of AI. Funding is a challenge, especially given that government agencies and multinationals in the United States, Europe and China invest billions of dollars annually in AI efforts. For this reason, philanthropic support for the center is a major priority for the Weizmann Institute, as well as the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute, which raises funds in the United States for the institute.

“It’s true we can’t compete with China’s budget, or the resources Google has. But we can make some fundamental, deep insight into this subject,” Bagon said. “Whereas companies like Facebook and Google are very much driven by business, we have the luxury of asking questions that other people don’t have the patience or the attention span to ask. We don’t even know these questions yet — let alone the answers to them.”

Prominent mathematician Boaz Nadler is also part of the team at the new AI center. His current research focuses on large data sets and their theoretical and practical applications — specifically how to find outliers and remove “noise” when fusing information from varying sources.

“Crowdsourcing is when you give a series of tasks to many different people and they all give you their answers,” he said. “You don’t know how accurate or inaccurate they are, yet you’d like to combine them and get an answer that’s even more accurate.”

Dramatically increased computing power is driving the AI revolution, much the same way the early 20th century saw a revolution in physics and the 1950s was defined by the computer revolution, Nadler said.

“Israel is known as the ‘Startup Nation,’ and many new startups today are based on machine learning and AI,” Nadler said. “This institute would like to put Weizmann at the forefront of academic research, but it will also help to train people who would then have the skills to go into industry. This is key for the continued success of Israeli companies.”

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science, which develops philanthropic support for the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, one of the world’s premier scientific research institutions. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.