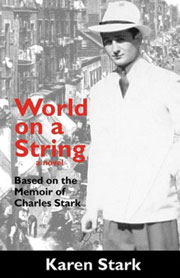

“World on a String,” by Karen Stark, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2012), available through Amazon.com in paperback or on Kindle Whether you knew Kansas City designer Charlie Stark or not, you’re in for one helluva ride with “World on a String,” a fictionalized account of his early years growing up on the streets of the squalid lower East Side of New York City in the 1920s, one of 11 people living in a two-room tenement slum.

Whether you knew Kansas City designer Charlie Stark or not, you’re in for one helluva ride with “World on a String,” a fictionalized account of his early years growing up on the streets of the squalid lower East Side of New York City in the 1920s, one of 11 people living in a two-room tenement slum.

Charlie Stark’s daughter, Karen Stark, has brought to vivid life the adversities and poverty her father overcame to build his career. While the book is fiction, Karen Stark says about 80 percent of it is absolutely true, much of it based on Charlie Stark’s memoir.

Stark, who grew up in Kansas City, Mo., said people here who knew him remember Charlie Stark for “his humor, wit, bravado, excitement, great imagination and ability to be a tremendous storyteller and schmoozer. They’ll remember some of these really beautiful places he created. But what they don’t know is the life he led before he came to Kansas City.

“They don’t now the tremendous hardship he lived and survived as a little boy, … the things that motivated him, that shaped his life and shaped him into the man he became,” she said.

Although the Starks were not affiliated with any synagogue, they did observe Jewish holidays and Stark said her parents spoke to one another in Yiddish at home.

Kansas City designer Charlie Stark came to Kansas City in 1932 at the age of 22, on his way to Hollywood to work as a set designer in the film industry. His stop here was just to visit relatives. It was the Depression, times were hard and jobs practically nil. To help his relatives, Charlie went out and found a job almost immediately designing window displays for department stores. His relatives were so impressed that, his daughter says, he thought maybe he could be a big fish in a little pond, so he stayed. Window displays grew into more design jobs, which led to creating restaurant interiors that looked like theater sets.

Charlie Stark came to Kansas City in 1932 at the age of 22, on his way to Hollywood to work as a set designer in the film industry. His stop here was just to visit relatives. It was the Depression, times were hard and jobs practically nil. To help his relatives, Charlie went out and found a job almost immediately designing window displays for department stores. His relatives were so impressed that, his daughter says, he thought maybe he could be a big fish in a little pond, so he stayed. Window displays grew into more design jobs, which led to creating restaurant interiors that looked like theater sets.

A club called The Castaways on Main Street was one of his designs.

“He created this whole South Sea Island ambience where an entire wall was a waterfall with beautiful tropical and exotic flowers placed strategically into the rocks of the waterfall,” Karen Stark said in a telephone interview from her home in Durham, N.C.

“Because my dad came from such a poor, impoverished background, everything had to be class.”

Another restaurant he designed was Lusco’s Lodge at about 83rd and Wornall, owned by Tudie Lusco.

“(My dad) said, ‘Tudie, I’m gonna make you this lodge that’s going to look like the Swiss Alps.’ And sure enough, he made a whole wall look like a mountainside with snow; he had a motorized ski lift going up it. … You felt like you were looking out the windows of a ski lodge,” Stark said.

Charlie was still designing restaurants into his 70s. According to Stark, in the early 1980s, one of the sons of Jasper Mirabile (of the famed Jasper’s) hired Charlie to do the interior of a new Italian restaurant called The Trattoria at 75th and Wornall.

“It doesn’t exist anymore,” Stark said. “My dad made the entire interior look like you were sitting in an Italian courtyard between two buildings. … You felt like you were in Venice.

“Up to the age of 87, he was still schmoozing and trying to convince people he was going to make something gorgeous. And I guarantee you there are probably dozens of people still in Kansas City who remember Charlie Stark coming in and saying, ‘Don’t worry. I’m gonna make you a showplace, I’m gonna make you a palace.’ ”

Trips to the Nelson

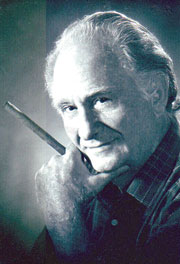

Although Charlie never had any formal training, he had a tremendous knowledge of art. Stark recalls that as a little girl, her dad would take her to the Nelson Art Gallery every Sunday where they would walk through the galleries and Charlie would scrutinize the paintings.

“He would just ramble on in his thick New York accent” about some Renaissance painting, pointing to it with his ever present cigar, explaining to his daughter how “the artist took with the tip of his brush just a drop of cadmium red and then a little cadmium yellow ochre just on the edge of this cloud to make the sunset pop out at you.”

Much of Charlie’s knowledge came from working with Alexander Chertoff, a well-known set designer in the Yiddish theater and on Broadway, who Stark says was a great inspiration to her father.

But he learned a great deal from books as well. When he was just 15, he was hired to decorate a social club. He got the idea to make it look like a New England hunting club, so he went to the New York Public Library, got photos of the English countryside and found paintings of English noblemen chasing foxes during the hunt.

“He wanted to make it perfect, he wanted to make it classy,” Stark said. “So he was really self-taught and self-motivated.”

Creating a Foundation

Stark said her father had to be his own advocate because no one else took on that role.

“When you read the book, you see that nobody was tender toward Charlie as a kid,” she said. “He had no advocates, no mentors, he was always on his own. He had to have his own inner strength to survive. Because nobody else told him he was a good kid, he had to tell himself that he was a good kid. Nobody else told him he was talented. He had to convince himself he was talented.”

Like so many other poor minorities, her dad did not have the opportunities to reach his full potential. Stark said she’s hoping a publisher will pick up the book, enabling her to sell millions of copies in order to start a foundation in her father’s name that gives scholarships to minority students who want to have careers in the visual arts.

“Had my father been properly mentored, he could have been a museum-quality painter,” she said. “I believe that minority students need more breaks. My dad was a minority slum kid who needed a break and he needed mentoring and guidance and nurturing. And kids that are poor and disadvantaged don’t get that nurturing. That’s why this will go to minority students.”