Spirit of unity will eventually draw young Jews back to Judaism

According to a recent study by the ADL, anti-Semitism in America is the lowest it has ever been. Of course this is a good thing. Of course we want to eradicate anti-Semitism, and racism and bigotry and sexism and homophobia and every other kind of crazy baseless hate. But the effect of this widespread acceptance of, and even appreciation of, Jews in American life has had a sizeable effect on Jewish Identity: 20 percent of American Jews do not identify as religious. In our bright, glittery world of Woody Allen and Drake and hummus and chutzpah, we are liberated of the terrible stigma that has always marked us as other. This should be beautiful, this should be glorious, this should be the stuff of utopian fantasy! And yet.

According to a recent study by the ADL, anti-Semitism in America is the lowest it has ever been. Of course this is a good thing. Of course we want to eradicate anti-Semitism, and racism and bigotry and sexism and homophobia and every other kind of crazy baseless hate. But the effect of this widespread acceptance of, and even appreciation of, Jews in American life has had a sizeable effect on Jewish Identity: 20 percent of American Jews do not identify as religious. In our bright, glittery world of Woody Allen and Drake and hummus and chutzpah, we are liberated of the terrible stigma that has always marked us as other. This should be beautiful, this should be glorious, this should be the stuff of utopian fantasy! And yet.

Here I am now with this terrible luxury, this magnificent burden, of choice. I have the ability to choose Judaism, or not to choose it. I am not branded, segregated, or shunned by the circumstances of my birth; I am amazingly, terrifyingly free. For many young American Jews, this means religion-lite, religion in small, calorie-free portions. A brisket sandwich, sure. A little Heineken and hamantaschen when Purim rolls around, no problem. A Friday night service? That’s a bit much, now, giving up some of my Friday night to participate in a tradition I have little connection to or interest in maintaining. Why should I, the wicked son, participate in something arcane and musty and confining? I have no incentive. And therein lies the tragedy.

At the 2013 Jewish Federations of North American General Assembly held last month in Israel, I met Jews from Poland, England, France and an array of other places. Places where, I was chagrined to learn, anti-Semitism is not the lowest it has ever been; rather, it is on the rise. Thus the young adults I met from those countries were fighting, still, for the freedom to be Jewish. Fighting! For what so many American Jews give up voluntarily, thoughtlessly, every one an Esau throwing his birthright at a pot of lentils. In an environment of openness and tolerance, where Jews are not held together by the threat of external forces, we must find a concrete way to retain Jewish identity and encourage its continuation.

The greatest accomplishment of the General Assembly of 2013 was the ingathering of so many cognizant, clever, and vibrant young Jews: Jews from all across North America as well as the world over, Jews with brilliant, enterprising minds and fresh ideas and well-thought-out opinions derived from formative experiences. We learned so much just from being in the same room with each other. Sharing our beliefs and passions and ideas enriched our sense of Jewishness and of belongingness, which really boils down to being the same thing. Judaism is a way of life built on community, on togetherness, on belonging to something created by individuals and yet greater than any individual. Together, we hold the future of our people in our young, unlined palms, and it is that spirit of unity, and the strength of that unity, which will eventually draw young, apathetic Jews back to Judaism.

Samantha Oppenheimer is the daughter of Carla and Scott Oppenheimer and a member of Congregation Beth Shalom. She is currently spending the year on Masa’s Israel Service Fellows program, teaching English at a rehabilitation village for troubled youth, planting and maintaining community gardens for older immigrant communities and various other volunteering placements.

When I told people I was in the middle of reading a book about Allan Sherman, I was surprised how few people even recognized the name, including people from my own generation, who might be expected to remember this comic genius who was at one time one of the most popular entertainers in America, whose comedy albums, beginning with “My Son, the Folk Singer” rivalled the albums of the best-known singers of the era on Billboard’s charts. At best, some may remember “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah,” a song about a homesick boy at summer camp.

When I told people I was in the middle of reading a book about Allan Sherman, I was surprised how few people even recognized the name, including people from my own generation, who might be expected to remember this comic genius who was at one time one of the most popular entertainers in America, whose comedy albums, beginning with “My Son, the Folk Singer” rivalled the albums of the best-known singers of the era on Billboard’s charts. At best, some may remember “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah,” a song about a homesick boy at summer camp. I read with great interest Barbara Bayer’s commentary/response to the community conversation regarding the Pew Research study of which I was a panel participant. My admiration and respect for all of my fellow participants was affirmed during the evening. I was and am appreciative for the opportunity to share my views and the work of my Congregation Kol Ami with the community. However, there is one inaccuracy in the article that requires clarification.

I read with great interest Barbara Bayer’s commentary/response to the community conversation regarding the Pew Research study of which I was a panel participant. My admiration and respect for all of my fellow participants was affirmed during the evening. I was and am appreciative for the opportunity to share my views and the work of my Congregation Kol Ami with the community. However, there is one inaccuracy in the article that requires clarification. For those who were wondering, the sky is not falling. In fact, as one panelist so eloquently put it last week, it would be strategically unwise to be pessimistic.

For those who were wondering, the sky is not falling. In fact, as one panelist so eloquently put it last week, it would be strategically unwise to be pessimistic. Taboo subjects hide in every facet of our society. Shame and stigma create a protective force around the topics, allowing them to thrive and reproduce unhindered by social conventions.

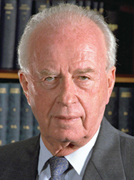

Taboo subjects hide in every facet of our society. Shame and stigma create a protective force around the topics, allowing them to thrive and reproduce unhindered by social conventions. When Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated, I was there. I remember that moment vividly to this day. It was Nov. 4, 1995. I was with my family and a full bus from our kibbutz. The energy was high, the crowd was huge and it felt like change was in the air. And then, three shots were fired … three shots that changed history for the State of Israel. When Israelis voted the Labor Party into government in June 1992, with Yitzhak Rabin at its helm, they knew well what they were getting. Here was a man who had been in public life for more than 40 years. When he became prime minister for the first time in 1974, he had been the first native-born Israeli (sabra) to attain the post. His astonishingly successful military record, no-nonsense speaking style, gravelly voice and oddly shy little smile were as familiar to Israelis as would be the mannerisms of a favorite uncle. Yet, in a short span, they would meet a new Yitzhak Rabin — a great war commander and implacable foe of the PLO transformed into a soldier for peace, and a Nobel laureate. And so, in November 1995, when this first-ever sabra/prime minister became the first-ever Israeli prime minister to be assassinated in office — and by a young Jew, no less — Israelis came to know with horror and grief what they had lost.Rabin’s assassination took place at a big peace rally, supporting him and the peace process. Everyone I was with was excited about this rally. Things in Israel were changing and a new era was about to begin … my parents were not about to let my siblings and I miss that. I was only 11 years old at the time, and didn’t understand much of what was going on around me. Still, it was educational. Taking part in such a historic event definitely had an impact on a girl like me.

When Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated, I was there. I remember that moment vividly to this day. It was Nov. 4, 1995. I was with my family and a full bus from our kibbutz. The energy was high, the crowd was huge and it felt like change was in the air. And then, three shots were fired … three shots that changed history for the State of Israel. When Israelis voted the Labor Party into government in June 1992, with Yitzhak Rabin at its helm, they knew well what they were getting. Here was a man who had been in public life for more than 40 years. When he became prime minister for the first time in 1974, he had been the first native-born Israeli (sabra) to attain the post. His astonishingly successful military record, no-nonsense speaking style, gravelly voice and oddly shy little smile were as familiar to Israelis as would be the mannerisms of a favorite uncle. Yet, in a short span, they would meet a new Yitzhak Rabin — a great war commander and implacable foe of the PLO transformed into a soldier for peace, and a Nobel laureate. And so, in November 1995, when this first-ever sabra/prime minister became the first-ever Israeli prime minister to be assassinated in office — and by a young Jew, no less — Israelis came to know with horror and grief what they had lost.Rabin’s assassination took place at a big peace rally, supporting him and the peace process. Everyone I was with was excited about this rally. Things in Israel were changing and a new era was about to begin … my parents were not about to let my siblings and I miss that. I was only 11 years old at the time, and didn’t understand much of what was going on around me. Still, it was educational. Taking part in such a historic event definitely had an impact on a girl like me. in a row. My father grabbed my hand and we started running away from the area. I looked back and saw that same crowd running toward us like a herd.

in a row. My father grabbed my hand and we started running away from the area. I looked back and saw that same crowd running toward us like a herd.