It’s a few days before Pesach. The rush is on to simmer the dates and almonds with wine for charoset, cut all the vegetables for the big pot of fava bean soup, and roast the red and green peppers for chouchouka.

It’s a few days before Pesach. The rush is on to simmer the dates and almonds with wine for charoset, cut all the vegetables for the big pot of fava bean soup, and roast the red and green peppers for chouchouka.

What? This doesn’t sound like a “traditional” Passover menu — at least not to Jews whose grandparents came from Eastern Europe.

But if you’re Nathalie Chetrite Scharf and your parents are from Morocco and Algeria, this is exactly what you’re preparing.

Scharf, who was born in Aix-en-Provence, France, is a minority within a minority in greater Kansas City — a Sephardi Jew. The name describes those Jews whose ancestors didn’t originate in Europe or Russia, but stayed in the Middle East, the Maghreb--- (North Africa) or countries like Greece, Bulgaria and the former Yugoslav states.

When Nathalie was a little girl in France, she used to visit her grandparents in Morocco almost every summer. “The Jewish community (in Casablanca) was large and active,” she recalled. “I remember the smells and sounds of preparing for Shabbat. My grandparents had several maids, as was traditional at that time, and I would hang out with them as they went to the souk or prepared meals.” The men attended services Saturday mornings at any of Casablanca’s many synagogues while the women prepared the house for the huge meal that followed. “The traditional dish my grandmother served was dafina; it is similar to cholent with potatoes, eggs, wheat, meat, chickpeas and cooks all night,” she added.

And while she’s not making dafina for Passover, Nathalie will be reminiscing with her mother, Michele Chetrite, who arrived at the end of March from France. “My mother was born in Fez, Morocco, and my father was born in Algiers,” she added. “My father was sent to a yeshiva in Strasbourg, France, in 1962 after Algeria gained its independence and entered law school in Aix-en-Provence. My mother left Morocco after high school to also attend the law school in Aix; that’s where they met.”

When Nathalie was 16, she came to the United States as an exchange student and lived with a family in southern California. She earned her high school diploma and stayed for another year so she could apply to California State University, Northridge. “I didn’t know anyone there and it was a huge campus with 40,000 students,” she recalled. “On the first day of school, I went to the Hillel House to meet other Jewish students.” She met the Hillel president, too — the man who would become her husband — James Scharf, whose Kansas City grandparents were Holocaust survivors Sol and Jennie Blum.

When Nathalie was 16, she came to the United States as an exchange student and lived with a family in southern California. She earned her high school diploma and stayed for another year so she could apply to California State University, Northridge. “I didn’t know anyone there and it was a huge campus with 40,000 students,” she recalled. “On the first day of school, I went to the Hillel House to meet other Jewish students.” She met the Hillel president, too — the man who would become her husband — James Scharf, whose Kansas City grandparents were Holocaust survivors Sol and Jennie Blum.

The couple married in 1991 and moved here in 1993. James’ mother, Nata Scharf had already moved from southern California in order to be close to her parents and the rest of her KC family. “I applied to Washburn Law School in Topeka and was accepted,” Nathalie said, adding that after graduation the couple moved to New York, where their first daughter, Naomie, was born. They returned to KC for a short period, then it was on to France where daughter Kayla was born. After four years with Nathalie’s family, they returned once again to KC. Today Scharf works for the Department of Commerce, bringing in foreign investments to Kansas and assisting local businesses looking to export their products; her husband, who was a social worker, has just completed his student teaching in elementary education and special ed.

They’ve lived in Overland Park since 2003. Naomie, now 13, attends Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy, and Kayla, 9, goes to Cottonwood Point Elementary. The family belongs to Beth Shalom, where Naomie celebrated her Bat Mitzvah last fall — among family and friends from France, Italy and Morocco.

“Aside from my family, I really miss the rich culture and traditions of the Moroccan Jews,” Scharf admits. It’s difficult to find some of the ingredients she needs for her Moroccan recipes, so she awaits her mother’s trips and the exotic spices, pate’, and Passover cookies she brings with her. “It is getting easier to find things on the Internet, such as harissa (a combination of spices and hot chili peppers used to flavor many North African dishes) and now couscous is everywhere.”

Her daughters are aware of their backgrounds and are interested in learning more about their Sephardic heritage. But it is a challenge in Kansas. Unlike New York, where the Scharfs had Jewish friends of Sephardic descent, here Nathalie has been asked if she really is Jewish when she didn’t understand Yiddish words!

Nathalie’s background didn’t include stories of the shtetls in Poland and Russia. Instead, one grandmother sang her Ladino lullabies — a mixture of Hebrew and Spanish, and others spoke of the fresh fruit and vegetables, exotic spices and grilled lamb featured in the North African dishes unique to each Jewish holiday.

That fava bean soup, for example, is a staple of Moroccan sederim. According to Claudia Roden, author of “The Book of Jewish Food: an Odyssey from Samarkand to New York,” “fava beans are one of the foods the Jews hankered for during their Exodus from Egypt.” Roden grew up in Egypt, so her version was made only with “salt, pepper, lemon juice and flat-leafed parsley.”

The Moroccan recipe passed down from Scharf’s Moroccan grandmother, adds vegetables and is, according to Roden, “deliciously aromatic.”

Nathalie also remembers the “Bibhilou” ceremony many Sephardi Jews perform at their sederim each year. The leader takes the seder plate and holds it over the head of each guest around the table, while everyone sings “Ha lachma anya” from Hallel, the songs of praise recited during every Jewish festival holiday: Passover, Sukkot and Shavuot.

Sephardic doesn’t necessarily mean Spanish, Scharf explained, “though my mother’s family roots are certainly from there.” She can trace her family back to Spain from before the Inquisition; they also are related to the revered Baba Sali, the late Moroccan rabbi who helped bring a generation of Jews to Israel.

“I still have a few distant relatives in Morocco, though very few remain. Most moved to Israel, France and Canada.” She’s concerned about the recent uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen, and wonders if it will spread to Morocco. In 1956, Morocco was home to more than a quarter of a million Jews. Today, fewer than 5,000 live in its largest city Casablanca. Fez and Tatoun, where Scharf’s family once lived, are now home to only 100-150 Jews each.

Michele Chetrite is happy to be in Kansas City, enjoying her granddaughters and helping prepare for Passover. Nathalie trained in Aix to be a pastry chef, while James worked at the family’s hotel. So it’s her job to create the desserts, while her mother is responsible for the fava bean soup, meatballs with green peas, lamb with white truffles, carrot salad, and chouchouka — the roasted bell pepper salad.

“I feel it is my responsibility to teach my kids some of the traditions they will be able to carry-on. One of them — widely known and celebrated in Israel — is Mimouna, a festival that marks the end of Passover. It was an incredible experience in Morocco! I still remember this vividly,” Scharf recalled. “We would go from house to house partaking in special delicacies and just celebrating, playing traditional music and all wearing our best caftans. This went on until the early hours of the morning.” Scharf said the custom is to eat many sweets like maffleta, a crepe with honey, zaban — a homemade nougat with almonds, and mrouzia, a current preserve.

In addition to hosting her mother during Passover, Nathalie’s father Guy and brother, Alexandre, are flying in on Sunday as well. And her sister, Stephanie, is getting married in September in Aix. Not only will the entire family be going, but also Nathalie plans to stock up on her favorite spices, orange blossom water, and other specialties. After all, by then she’ll need them to make Gateau a l’Orange, a Moroccan orange cake served during Sukkot!

Soupe de fèves de Pessah

Fava Bean Soup for Pessah

1 kg (about 2.2 lbs) beef roast plus marrow bone

1 kg new potatoes

1 kg of fresh or frozen peeled fava beans

2 leeks

3 stalks of celery

2 carrots

cilantro

salt

pepper

curcuma (a type of turmeric)

oil

Season the meat and salt and pepper and brown on all sides. Remove the meat.

Wash, peel and dice all vegetables finely, except for the fava beans.

Sauté the vegetables (except fava beans) in the drippings from the meat, and add the meat and marrowbone. Add enough cold water to cover meat and vegetables. Cover and simmer until all vegetables are done.

Add the fava beans and cook an additional 10-15 minutes. Add the chopped coriander, salt, pepper and curcuma to taste.

Agneau aux terfasses

Lamb with white truffles

1kg lamb shoulder roast

oil

1 bunch saffron

4 garlic cloves

salt

pepper

1 kg canned white truffles (from Morocco)

Cut the meat into large chunks and season with salt and pepper on all sides. Sauté in the oil until the meat browns. Add a cup of water, the whole garlic cloves, saffron, salt and pepper. Cover and simmer for one hour.

Add the canned truffles and simmer an additional 30 minutes.

Moufleta

3 ¾ c. flour

1-½ c. warm (not boiling) water

Pinch of salt

Vegetable (not olive) oil, as needed

Place flour and salt in bowl. Scoop out a “well” in the middle and add water there. Mix, adding a little extra water if dough seems too dry. Mix together until a light and elastic dough is formed.

Divide dough into 15 to 20 small balls. Cover with dishtowel and let stand 30 minutes on a flat, well-oiled surface.

Oil hands and on oiled surface, roll dough into thin circles.

Spread small amount of oil in frying pan and cook mufleta over medium heat. Cook both sides. Pan does not need to be re-greased before cooking the rest of the mufletas.

Place on a plate and cover with dishtowel to keep them warm. Serve warm with butter and honey.

These may be frozen and re-heated in microwave. Makes 15 to 20 mufletas.

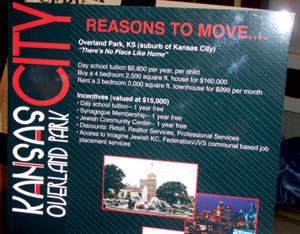

NEW YORK, NEW YORK — A contingency of congregants from BIAV trekked to New York last month to promote the congregation and the Kansas City area at the Orthodox Union’s Emerging Communities Fair. More than 1,000 people were there to explore viable alternatives to life in the Northeast. Eva Sokol organized the BIAV presentation, and led the group, which included Rabbi Daniel and Ayala Rockoff, BIAV President Andy Ernstein, Carol Katzman and Jason Sokol. Sokol said they spoke to approximately 80 families about our community. Many are interested in finding out more about Overland Park.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK — A contingency of congregants from BIAV trekked to New York last month to promote the congregation and the Kansas City area at the Orthodox Union’s Emerging Communities Fair. More than 1,000 people were there to explore viable alternatives to life in the Northeast. Eva Sokol organized the BIAV presentation, and led the group, which included Rabbi Daniel and Ayala Rockoff, BIAV President Andy Ernstein, Carol Katzman and Jason Sokol. Sokol said they spoke to approximately 80 families about our community. Many are interested in finding out more about Overland Park.

It’s a few days before Pesach. The rush is on to simmer the dates and almonds with wine for charoset, cut all the vegetables for the big pot of fava bean soup, and roast the red and green peppers for chouchouka.

It’s a few days before Pesach. The rush is on to simmer the dates and almonds with wine for charoset, cut all the vegetables for the big pot of fava bean soup, and roast the red and green peppers for chouchouka. When Nathalie was 16, she came to the United States as an exchange student and lived with a family in southern California. She earned her high school diploma and stayed for another year so she could apply to California State University, Northridge. “I didn’t know anyone there and it was a huge campus with 40,000 students,” she recalled. “On the first day of school, I went to the Hillel House to meet other Jewish students.” She met the Hillel president, too — the man who would become her husband — James Scharf, whose Kansas City grandparents were Holocaust survivors Sol and Jennie Blum.

When Nathalie was 16, she came to the United States as an exchange student and lived with a family in southern California. She earned her high school diploma and stayed for another year so she could apply to California State University, Northridge. “I didn’t know anyone there and it was a huge campus with 40,000 students,” she recalled. “On the first day of school, I went to the Hillel House to meet other Jewish students.” She met the Hillel president, too — the man who would become her husband — James Scharf, whose Kansas City grandparents were Holocaust survivors Sol and Jennie Blum. How many times have you sat with Zayde or Aunt Esther and promised yourself that sometime soon you will chat with him or her and capture all their life stories before they aren’t able to tell them anymore?

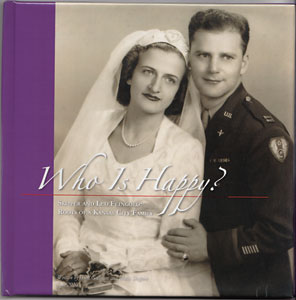

How many times have you sat with Zayde or Aunt Esther and promised yourself that sometime soon you will chat with him or her and capture all their life stories before they aren’t able to tell them anymore? Keepsake Chronicles is another Jewish-owned company helping people capture and preserve their life stories. Diane Wubbenhorst, a member of Congregation Kol Ami, and her business partner Jamie Thaemert, said Keepsake Chronicles has been in business since late February. The company, which holds a membership in the Association of Personal Historians, specializes in capturing, chronicling and producing people’s life stories using a unique story gathering process.

Keepsake Chronicles is another Jewish-owned company helping people capture and preserve their life stories. Diane Wubbenhorst, a member of Congregation Kol Ami, and her business partner Jamie Thaemert, said Keepsake Chronicles has been in business since late February. The company, which holds a membership in the Association of Personal Historians, specializes in capturing, chronicling and producing people’s life stories using a unique story gathering process. Edna Levy is a bundle of energy. In the classroom she curls up on a chair, feet tucked underneath, as she asks the women in her recent “Sheroes of the Bible” class to look at the text. “What’s the Hebrew used for the basket carrying Moses?” she asks. A student finds the word ‘teva’ and recalls it was used in the portion about Noah. It’s not just “a basket” Levy agrees, but something sturdier. Maybe there’s a parallel between Noah’s “saving humanity” and Moses’ potential “saving of the Jewish people.”

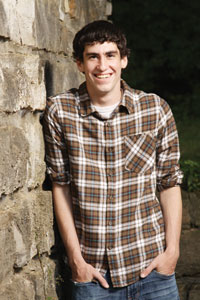

Edna Levy is a bundle of energy. In the classroom she curls up on a chair, feet tucked underneath, as she asks the women in her recent “Sheroes of the Bible” class to look at the text. “What’s the Hebrew used for the basket carrying Moses?” she asks. A student finds the word ‘teva’ and recalls it was used in the portion about Noah. It’s not just “a basket” Levy agrees, but something sturdier. Maybe there’s a parallel between Noah’s “saving humanity” and Moses’ potential “saving of the Jewish people.” If Adam Sitzman was to define his teenage years, it would take only four letters: BBYO. “I define myself in the Jewish community through BBYO,” Adam said. It is through BBYO that he has met great friends and learned leadership skills. And it is through BBYO that Adam was nominated to be this month’s Salute to Youth honoree.

If Adam Sitzman was to define his teenage years, it would take only four letters: BBYO. “I define myself in the Jewish community through BBYO,” Adam said. It is through BBYO that he has met great friends and learned leadership skills. And it is through BBYO that Adam was nominated to be this month’s Salute to Youth honoree. Asher’s is the face that immediately popped into my mind when I heard a school bus from Sha’ar HaNegev High School was hit by an anti-tank missile last Thursday (April 7), critically wounding Daniel Viflic, a 16-year-old student. (Editor’s note: At press time, Daniel Viflic’s condition had worsened. He went into a coma and has been unresponsive, in spite of exhaustive medical care.)

Asher’s is the face that immediately popped into my mind when I heard a school bus from Sha’ar HaNegev High School was hit by an anti-tank missile last Thursday (April 7), critically wounding Daniel Viflic, a 16-year-old student. (Editor’s note: At press time, Daniel Viflic’s condition had worsened. He went into a coma and has been unresponsive, in spite of exhaustive medical care.) DELIGHTFUL EVENING — It looked like everyone, including co-chairs David Porter and Patricia Werthan Uhlmann, were having a wonderful time Sunday night as the Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy celebrated its 45th anniversary. Two members of the original graduating class were in attendance — Debbie Sosland-Edelman and Harriet Puritz Almaleh. We were all treated to a video featuring some of the founders where we heard the hit line of the evening, delivered by Blanche Sosland. She reported that when they met with Hyman Brand for the very first time seeking his support, he called the group a bunch of “young punks.” Brand was so impressed with those “young punks” that in two weeks he raised enough money for the school to operate its first year.

DELIGHTFUL EVENING — It looked like everyone, including co-chairs David Porter and Patricia Werthan Uhlmann, were having a wonderful time Sunday night as the Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy celebrated its 45th anniversary. Two members of the original graduating class were in attendance — Debbie Sosland-Edelman and Harriet Puritz Almaleh. We were all treated to a video featuring some of the founders where we heard the hit line of the evening, delivered by Blanche Sosland. She reported that when they met with Hyman Brand for the very first time seeking his support, he called the group a bunch of “young punks.” Brand was so impressed with those “young punks” that in two weeks he raised enough money for the school to operate its first year. Plans are currently underway to launch a new reform congregation in Kansas City. Its new spiritual leader will be Rabbi Jacques Cukierkorn, who just severed his relationship with the New Reform Temple. (For more information, see below.) Known by the name Temple Israel for now, it held services for the first time Friday, April 1, at St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church in Overland Park. Rabbi Cukierkorn said services would be held there again tonight, Friday, April 8, at 6 p.m. at 12251 Antioch Road in Overland Park, and for the foreseeable future. For more information, contact Rabbi Cukierkorn at (913) 940-1011.

Plans are currently underway to launch a new reform congregation in Kansas City. Its new spiritual leader will be Rabbi Jacques Cukierkorn, who just severed his relationship with the New Reform Temple. (For more information, see below.) Known by the name Temple Israel for now, it held services for the first time Friday, April 1, at St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church in Overland Park. Rabbi Cukierkorn said services would be held there again tonight, Friday, April 8, at 6 p.m. at 12251 Antioch Road in Overland Park, and for the foreseeable future. For more information, contact Rabbi Cukierkorn at (913) 940-1011. Want to learn how to experience your Judaism in a new light. Check out what Rabbi Sharon Brous, The Temple, Congregation B’nai Jehduah’s guest scholar has to say tonight and tomorrow (April 8 and 9).

Want to learn how to experience your Judaism in a new light. Check out what Rabbi Sharon Brous, The Temple, Congregation B’nai Jehduah’s guest scholar has to say tonight and tomorrow (April 8 and 9). An estimated 1 billion people in the world go to bed hungry every night. That’s one in every seven people.

An estimated 1 billion people in the world go to bed hungry every night. That’s one in every seven people.