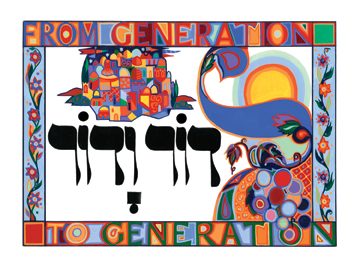

Most people look at Hebrew letters and just see an alphabet. Artist Mordechai Rosenstein sees shapes. In fact, he begins most of his paintings with Hebrew letters — working upside down.

Most people look at Hebrew letters and just see an alphabet. Artist Mordechai Rosenstein sees shapes. In fact, he begins most of his paintings with Hebrew letters — working upside down.

“I turn the paper, I start lettering backwards or upside down because the letters become abstract shapes,” Rosenstein says. “I have a lot more freedom to make them flow. But when it gets too far along, I have to turn the paper around.”

His paintings, tapestries, murals and silk screen prints come to vivid life through his vibrant use of color, using gouache, an opaque watercolor. He creates prints using ink jet printing, or giclée.

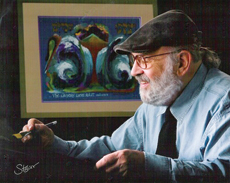

Rosenstein will be artist-in-residence at Congregation Beth Shalom from Oct. 9 through 13 and at The Temple, Congregation B’nai Jehudah Oct. 15 through 20. In addition, he will display about 40 of his works at the Jewish Arts Festival on Sunday, Oct. 6.

Artist in residence

Rosenstein will address the congregations on a Friday night, talking about how he became an artist and has made a living at it for 35 years.

“It’s kind of a miracle or a phenomenon,” he says. “The art world is 3 feet wide and the Jewish art world is 1 inch wide.”

On Saturday, Oct. 11, he will give the d’var Torah at Beth Shalom and show certain pieces of his influenced by the Torah, like Jacob wrestling with the angel.

“The Torah paints the picture; all you have to do is put it down on paper. The Torah sometimes gives you the whole story, it’s all painted for you,” says the Philadelphia artist. “Usually on Saturday night, we have a wine and cheese and I do a slide presentation.”

He will also talk about some of his one-of-a-kind pieces.

Rosenstein will conduct activities with preschool and religious school students at both synagogues, working with calligraphy.

“I let them do their name, if they can, in Hebrew characters made out of objects,” he says. “Like inside the letter Mem, the first letter of my name, I have a big round matzah or a pizza, and the last letter is a Yud and I use a football. I say, ‘Can you read this?’ They read it, but then they see that each letter is made up of familiar objects.

“We’re not trying to make calligraphers in 45 minutes and I usually dissect one piece. We go over it and they see the letters, they see the colors and it’s a good session. Sometimes we invite the parents and have some projects for them.”

Rosenstein says he never has a schedule ahead of time as artist in residence, but over the years he and his partner, Barry Magen, have made it into a whole program, so he doesn’t get nervous about it.

For Beth Shalom’s Peltzman class and B’nai Jehudah’s Sisterhood, Rosenstein says he will probably do a slide show or let them do some “coloring in.” They’re given a black outline of Hebrew words or some dancing figures and then color them.

“It looks like a stained glass window when it’s done.” Rosenstein says. “Or they may want to write their name and get creative. But I can speak about some original pieces; they’re interested in that also. We’ve done it before many times. Whatever group it is, whatever they present, we’ll have different projects and we’ll make them fit.”

During the day, throughout the week, Rosenstein says he usually creates an original piece of art, which is added to his inventory of works. He goes in with a blank piece of paper, the rabbi gives him a saying and he goes to work. Children and their parents coming and going are able to watch the painting grow, and even give their input.

“They get interested in it and I always ask them do you have any ideas or what do you think I should do, and sometimes they get into it,” he says.

The art of Hebrew letters

From the time he was a child, Rosenstein says he was fascinated with Hebrew letters and still uses them as the basis of most of his designs.

From the time he was a child, Rosenstein says he was fascinated with Hebrew letters and still uses them as the basis of most of his designs.

“My generation went to Hebrew school at age 6. After school you had to put up your books and get your writing book and go sit for an hour in the synagogue basement. So I was intrigued with the letters,” he says. “And we used to get a Hebrew newspaper; my father read it every day. Someone else could look at it and it just didn’t affect them, but for some reason I really enjoyed the letters. They became forms.”

So when he demonstrates to children how he begins his paintings, he says all of a sudden they pick up that he’s writing upside down and backwards.

“I can visualize the letters, so I don’t know what that’s all about. I think a lot of artists are dyslexic,” he says. “Sixty-five years ago I had trouble reading and they didn’t know why.”

The teachers would put six or seven children in a room once a week and make them read because they didn’t think the children read enough. “But I can write upside down in English, Hebrew, it doesn’t matter. I could always do it,” Rosenstein explained.

Although he has been compared to Marc Chagall, Rosenstein says he always wanted to be like Henri Matisse and Alexander Calder, “the primaries.” He says he was influenced by the abstract expressionist school.

“My teacher was Franz Kline; I studied with him at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art (now the University of the Arts) in 1952.”

With the Bible as his inspiration, Rosenstein says he hasn’t yet scratched the surface.

“When I want to do a piece I study it, I research it,” he says. “Plus in synagogue we review it every week. My favorite joke is ‘didn’t we read this last year?’ You read it every year and believe it or not you find new things.

“We haven’t even done the Prophets yet. But the imagery that the Prophets give, their beautiful, magnificent visions … like Ezekial, which is real mysterious — a wheel within a wheel. Anyway, we’ll never run out. I will run out before the Bible runs out.”